The Uncommon People project is one close to my heart. Its story not only deals with some of my favourite things (Sheffield, music, design, innovation), but also illustrates the rise and fall of technology we once worshipped over a relatively short time.

The Background

In 2009, in a previous company, we were working on the brand, website and promotional work for Sheffield’s annual Sensoria Festival (something I’m still happy to be involved with) when they laid down a challenge…

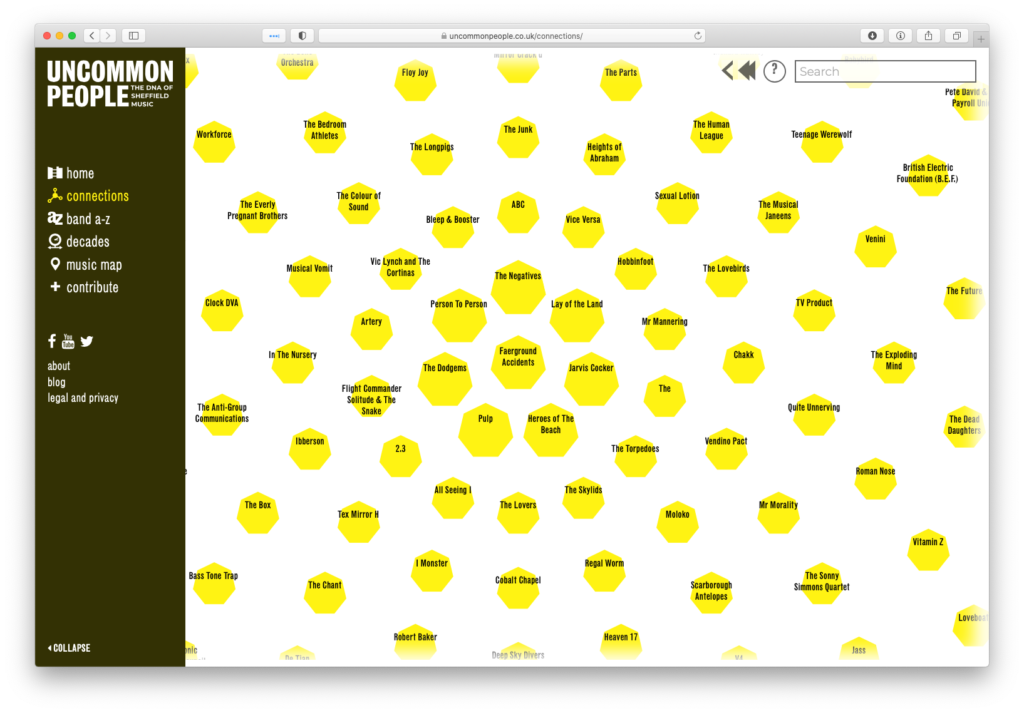

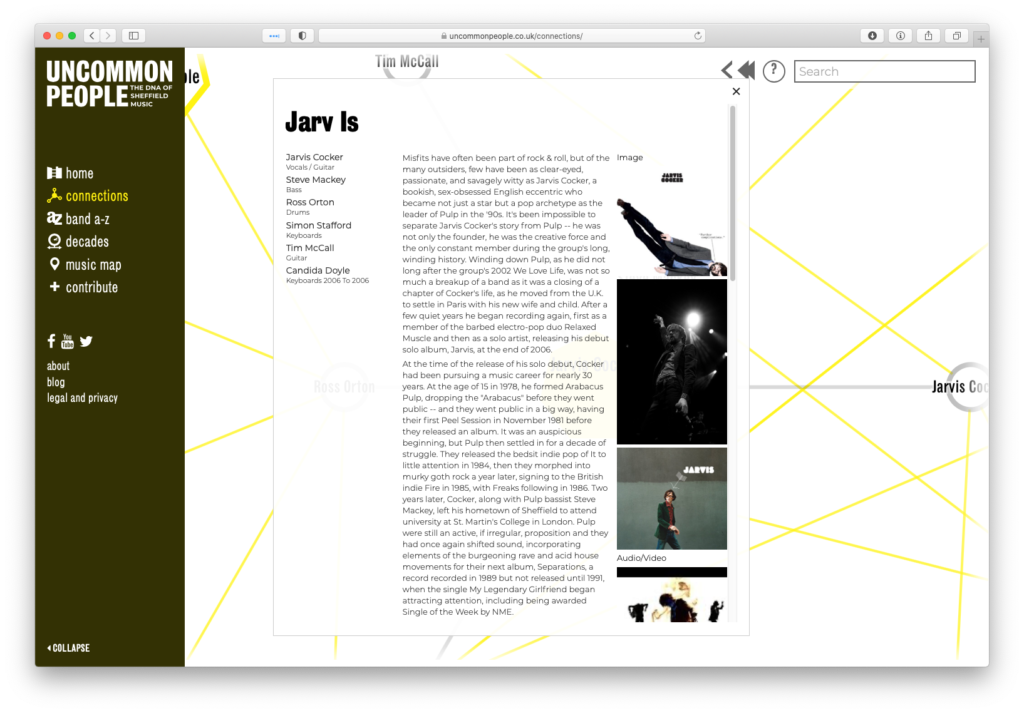

Sheffield is well-known for having had a vibrant and innovative music scene since the 1950s, and one characteristic has been that so many artists have swapped around, been in each other’s bands, gone solo, started other projects or worked as guests on other bands’ work. Our task was to create and online ‘family tree’ from the raw data being compiled by Sensoria’s researchers that would both separate all of Sheffield’s musicians out but also show how they were all connected to each other as well…all in a living, breathing and growing format. So, like Jarvis, I said “I’ll see what I can do,” and Uncommon People was born.

After a successful branding phase, a lot of research and several brainstorming sessions we came up with an idea of something that combined DNA mapping, a family tree and an interactive timeline. Then we just had to work out how to make it with the available technology…

The Flash Era

At the time Flash was the perfect (well, the only) choice to enable us to do what we needed to do, which was to interrogate our database and then build an online interactive, animated, navigable 3D map of connections between all of Sheffield’s bands and musicians.

It’s hard to think that in those days (which weren’t really all that long ago) Adobe Flash was The Big Thing and there was no such thing as an iPad. At that time, smartphones were in their infancy and there was certainly very little appetite for the mobile web (WAP pages anyone?). You created your Flash application, animation, game, intro, etc. using Adobe’s (originally Macromedia’s) Flash editor which was a combined vector drawing, design, animation, sequencing, audio and coding environment. When it was finished you exported your work as a single, highly compressed .swf file and dropped it onto a normal web page just like you would a JPEG or PNG image. Any web browser that had the Flash plugin installed (which, at the time, was all of them) could then uncompress and play back any Flash items on a page.

Interactive Flash animations could be entire websites in themselves or fully fledged video games that ran in your browser. Even traditional HTML websites would have little pieces of Flash animation scattered around them or a cheeky intro screen. Flash was seemingly inextricably threaded into the fabric of the web.

As a system for animating vector graphics and dealing with sound, video and images (something normal web pages would never have been able to do), Flash was unsurpassed. The web was flooded with innovative websites, games and web apps, the like of which had never been seen before. Another major win was that its video format (.flv) was really easy to create and embed which lead to it being adopted by YouTube and other major players as its primary video format.

Success came at a price, however – Flash’s popularity and ubiquity made it a target for hackers and, because it ran in any web browser, could be made to attack any operating system equally easily as it could be given access to the host’s filesystem.

Adobe’s regular (and increasingly annoying) Flash updates themselves were also targeted – hackers would set up websites with dialogue boxes on which mimicked Adobe’s familiar “You need to update Flash” message; users just pressed the “OK” button and downloaded all sorts of malware to their system. You thought you were installing a security upgrade to stop the latest hacks but you were, in fact, installing the next generation of deadly viruses and trojans.

The other issue with Flash was its sheer greed. Every new version demanded more processing power and memory from the machine it was running on. Looking at a really ‘flashy’ Flash website could cause everything else on your computer to stop dead, as it would quite happily eat 100% of your processor’s capacity to do its stuff. Some older browsers, operating systems or machines themselves weren’t able to handle some newer Flash content and started to be excluded from later updates and so the cross-platform compatibility and consistency started to break down, with many users giving up on the technology when faced with having to buy a new computer to use it on.

Early iPhones and, later, iPads were completely unable to cope and Apple kept a low-key approach to Flash, overlooking it completely in the original versions of iOS: the mobile Safari browser had no Flash plugin. This angered a lot of people, but as Apple became the dominant force in mobile computing they were able to call the shots. Steve Jobs finally came out and said that Flash would never be allowed on Apple devices – they had tried it and decided that due to the security issues and the fact your battery would only last a few minutes from its huge demands, that we needed something better: the technology was already out there (the next generation of HTML, JavaScript and SVG vector graphics) and it was all free and open – we just just had to learn to put it all together. His (in)famous “thoughts on Flash” open letter of April 2010 clinically and logically destroyed Flash point by point and split opinion, with those who disagreed (mainly Adobe) citing the fact that Flash’s potential to be used to build applications which could generate revenue outside Apple’s App Store ecosystem was what was really behind it all.

Decline

How things change! Phones and tablets now rule (the majority of websites now report that they are viewed more on mobile devices than computers) and, as of 1st January 2021, Adobe has finally declared Flash dead, after a long illness.

According to chromium.org, the number of times a web user enocuntered at least one page with Flash content in one day was 80% in 2014. By 2019 it was 2.5%! During this five year decline, new versions of web browsers had shifted from installing with the Flash plugin installed and already activated by default to making it an optional extra and then to completely ignoring it.

As we sunk into a recession and the Uncommon People site became less and less usable due to the diminishing popularity of Flash in people’s browsers, the project languished. Neither funding nor a suitable new technology to replace Flash were forthcoming. Mobile usage tipped the opposite direction and more and more websites started reporting that their mobile / tablet visits were now higher than those from “normal” computers. Flash’s performance and security issues on Android devices coupled with Adobe’s slowness in remedying them also seemed to prove that Apple’s predictions were more than just sour grapes.

One other major problem with Flash is that every time somebody said its name, somebody else in the office always felt compelled to shout “…aaaahaaa…Saviour of the Universe!” in response. I won’t miss that bit.

A Glimmer of Hope

Then, at the end of 2019 some funding unexpectedly became available and Sensoria contacted me (now installed here at Azzure Creative) about the possibility of breathing some new life into the Uncommon People site with a modern rebuild and a budget for some research to get the artist data up to the present day.

We’d often spoken about the possibility of redoing the site, as HTML5 and JavaScript had matured over the years to enable us to do a lot of what we needed Flash for in the early days. A major factor is that these technologies are open, work very well on mobile devices and we would finally be able to have the cross-platform solution we always wanted without excluding huge parts of our audience. In fact, this is exactly what Steve Jobs suggested and predicted in his letter, and even Adobe seem to agree now: any ex-Flash developer who’s had a bit of time away from it and, like me, chances upon Adobe Animate will be pleasantly surprised to find a rather familiar looking piece of software – it’s the Flash development app (rebadged in 2016) but now set up to output its creations in JavaScript, HTML5 and SVG formats. Its Flash .swf generation capabilities are still buried away in there, described as “legacy”.

One of the important features of Uncommon People was that the project should continue to grow. It depends on contributions from the public to keep track of the changing face of Sheffield’s music. Audio clips, video, photos and stories uploaded to the site gives it a sense of community. Musicians featured on the site often pop up themselves to add extra facts about their career. The new approach allows that to happen without the fear of obsolescence or restricting access to some users.

We learned a lot. It turned out that pretty much everyone in Sheffield except me has been a member of Pulp at some point in their life, that Richard Hawley has been in every band ever and Def Leppard have no friends. More importantly, we learned that basing a website on a less-than-open technology, despite its seemingly universal popularity, is a risk if what you are building is intended to have a long shelf-life. Something controlled by one organisation can be mismanaged into the ground or just taken away from you without any way of stopping it (one day, when I can bring myself to, I’ll write an article about FreeHand and GoLive – another sorry Adobe story).

I’m sure as Sensoria re-launch the Uncommon People site, the Sheffield music scene will keep changing and evolving and innovating as it always has. This time, however, the technology that powers Uncommon People should be able to keep up with it.